Human Rights!

Bloody Human Rights!

A Queen Mary University of London public engagement project in association with Amnesty International and Menagerie Theatre Company.

2 Weeks. 7 Performances. 500 Spectactors. 10 Solutions.

1 Future.

The Well and the issues behind it

The Well is the most traditional of the three plays that make up the Human Rights! Bloody Human Rights! trilogy in that it contains a complete story. It explores a number of issues but, centrally, a lack of community consultation, something which is a common phenomenon within cases of business and human rights abuse. Occasionally this makes headlines when communities are successful in getting their voices heard, as with tribal community victories in India over Vedanta Resources PLC in 2013 and 2014. Mostly, however, affected communities find it hard to get their voice heard once decisions have been made without them. In this situation, BEW India, the fictional Indian subsidiary of a British company, has been granted water collection rights throughout the state of Orissa in India. They have provided information and held meetings in the national regional capitals, and issued notices in the official languages of English and Hindi. Additionally, the company is seeking a signed consent from each community for closing and damming wells and rivers. Unfortunately for BEW employee, Trevor, the community he has been parachuted into knows nothing of the privatisation plans, as they speak a minority language and no consultations were held nearby.

Access to water was chosen as the central issue in the first play because everyone understands what is at stake – life. Access to water is also a human right because of its vital connection with life and the realisation of other human rights. The community will die if BEW close the well. However, the well is also a source of disease; Basanti herself has been sick, and BEW is right that it needs to be cleaned. However, it is not clear Basanti understands that “a tap and a meter” means the water will become a commodity they must pay for, and this subsistence community cannot afford to pay for water. In short, she and the community need your help.

Trevor is ably assisted by the local mayor who translates for him and is keen on the privatisation as it will bring health and jobs. In introducing the mayor we also encounter another common phenomenon which is that affected communities in business human rights cases are often split between those who will benefit from the presence of the company in their community and those who will be disadvantaged. In this case Basanti and her community will die if they close the well, whereas the mayor and his constituency will benefit. The mayor also introduces the corrosive issue of corruption into the mix and the problems that multinational corporations have ensuring that their compliance policies have impact on the ground. From BEW’s point of view they have done everything right: held consultations, provided ample information and notices, engaged with the democratically elected mayor, yet everything is not all right - the village community leader responsible for the well won’t sign the consent form - indeed does not understand why this foolish man wants to kill them.

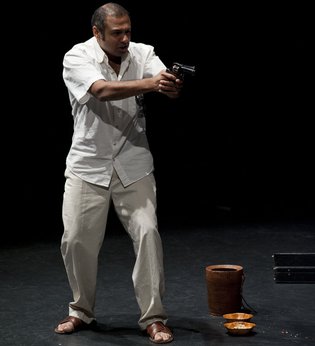

The play also explores the corporation’s reliance on contract and confidentiality. Trevor's insistence on Basanti signing a consent form, his refusal to let her see the collection rights agreement, and his insistence on protecting those collection rights (here stopping the community collecting water in their mouths) are reflections of real world behaviour by corporations – perhaps most famously in Cochabamba in Bolivia, but also common elsewhere. Therein lies the range of core issues the audience has to try to fix. BEW must get her signature to close the well but she must make sure there is water for the community. If the conflict cannot be resolved then, as the play is scripted - tragedy ensues.

Researching The Well

Those familiar with high profile business human rights abuse cases will recognise the fictionalised mash up of issues from current water privatisations in India, cases such as Vedanta's Orissa dispute, water privatisation cases in Bolivia, Argentina, and Tanzania (there are more resources on these water cases in the research section of The Trial) and the case of Union Carbide's Bhopal disaster in 1984, which remains the worlds worst industrial disaster, still generating legal actions some 30 years later. It is no coincidence that these cases are well known. They all contain a remarkable and too often tragic story behind which lies important mistakes with regard to community consent and the shifting of responsibility and liability by the public and private sector. Mistakes that continue to be made in 2014.

Do It Yourself

If you fancy yourself as an actor, director or facilitator/difficultator, here is your big chance. Have a look at the "How it works" film here and use our script for The Well

below plus the film of the play above. You can then perform The Well and see if your audience of spectactors can fix the problems by suggesting action to your actors. Or they may even throw out your actors and become the mayor, Trevor or Basanti. Remember, you need not just those prepared to act, you also need people who are willing to read up on the issues with the resources provided and argue their character's case. It is important that they stay in character no matter what they really believe. That said, we leave it up to you as to how you do it, all we ask is that you email us here to let us know that you are using the scripts and that you acknowledge the Human Rights! Bloody Human Rights! project when you perform them. Or you may simply want to read the script and contemplate the issues - feel free - but if you feel moved, let us know what you think in the comment box below.

Fix it

In trying to fix the problem in The Well audiences invariably got onstage and helped Basanti by translating and advising her. This often assisted in bringing about a real negotiation with BEW about temporary access to water while the well was being cleaned, and the price of water afterwards. Sometimes, however, the audience despaired at finding a way out of the roles the characters had been given. See if you can do it better with our Do It Yourself Kit opposite.

As written the issues could not be resolved and for the second play we move Continents to London where

the consequences of Basanti's death land on the desk of the new UK Minister for Business.

Did you fix it? Tell us what you would do

The driving ambition behind the Human Rights! Bloody Human Rights! project was a shared need by Professor Alan Dignam and Amnesty International to raise public awareness of important but complex aspects of business involvement in human rights abuse. This is the outcome.

If you performed The Well tell us about your experience and solutions or if not, just tell us what you think by leaving a comment on our home page. Business and government engagement on the issues raised here will only increase if public pressure is brought. That future starts with you.

Copyright © Professor Alan Dignam All Rights Reserved